H.264 is Magic

H.264 is a video compression codec standard. It is ubiquitous - internet video, Blu-ray, phones, security cameras, drones, everything. Everything uses H.264 now.

H.264 is a remarkable piece of technology. It is the result of 30+ years of work with one single goal: To reduce the bandwidth required for transmission of full-motion video.

Technically, it is very interesting. This post will give insight into some of the details at a high level - I hope to not bore you too much with the intricacies. Also note that many of the concepts explained here apply to video compression in general, and not just H.264.

Why even compress anything?

A simple uncompressed video file will contain an array of 2D buffers containing pixel data for each frame. So it's a 3D (2 spatial dimensions and 1 temporal) array of bytes. Each pixel takes 3 bytes to store - one byte each for the three primary colors (red, green and blue).

1080p @ 60 Hz = 1920x1080x60x3 => ~370 MB/sec of raw data.

This is next to impossible to deal with. A 50GB Blu-ray disk will only hold ~2 mins. You can't move it anywhere fast. Even SSDs have trouble dumping this straight from RAM to Disk[^1].

So yeah. We need compression.

Why H.264 compression?

Yes, I will answer this. But first let me show you something. Here is the Apple Homepage:

I captured the screen of this home page and produced two files:

- PNG screenshot of the Apple homepage 1015KB

- 5 Second 60fps H.264 video of the same Apple homepage 175KB

Eh. What? Those file sizes look switched.

No, they're right. The H.264 video, 300 frames long is 175KB. A single frame of that video in PNG is 1015KB.

It looks like we're storing 300 times the amount of data in the video. But the file size is a fifth. So H.264 would seem to be 1500x as efficient as PNG.

How is this even possible? All right, what's the trick?

There are very many tricks! H.264 uses all the tricks you can think of (and tons you can't think of). Let's go through the important ones.

Shedding weight

Imagine you're building a car for street racing. You need to go faster. What is the first thing you do? You shed some weight. Your car weighs 3000 lbs. You throw away stuff you don't need. Those back seats? pfft. Chuck those. That subwoofer? Gone. No music for you. Air Conditioning? Yeah, ditch it. Transmission? Ye..no. Wait! We're gonna need that.

You remove everything except the things that matter.

This concept of throwing away bits you don't need to save space is called lossy compression. H.264 is a lossy codec - it throws away less important bits and only keeps the important bits.

PNG is a lossless codec. It means that nothing is thrown away. Bit for bit, the original source image can be recovered from a PNG encoded image.

Important bits? How does the algorithm know what bits in my frame are important?

There are few obvious ways to trim out images. Maybe the top right quadrant is useless all the time. So maybe we can zero out those pixels and discard that quadrant. We would use only 3/4th of the space we need. ~2200 lbs now. Or maybe we can crop out a thick border around the edges of the frame, the important stuff is in the middle anyway. Yes, you could do these. But H.264 doesn't do this.

What does H.264 actually do?

H.264, like other lossy image algorithms, discards detail information. Here is a close-up of the original compared with the image post-discard.

See how the compressed one does not show the holes in the speaker grills in the MacBook Pro? If you don't zoom in, you would even notice the difference. The image on the right weighs in at 7% the size of the original - and we haven't even compressed the image in the traditional sense. Imagine your car weighed just 200 lbs!

7% wow! How do you discard detail information like that?

For this we need a quick math lesson.

Information Entropy

Now we're getting to the juicy bits! Ha puns! If you took an information theory class, you might remember information entropy. Information entropy is the number of bits required to represent some information. Note that it is not simply the size of some dataset. It is minimum number of bits that must be used to represent all the information contained in a dataset.

For example, if your dataset is the result of a single coin toss, you need 1 bit of entropy. If you have record two coin tosses, you'll need 2 bits. Makes sense?

Suppose you have some strange coin - you've tossed it 10 times, and every time it lands on heads. How would you describe this information to someone? You wouldn't say HHHHHHHHH. You would just say "10 tosses, all heads" - bam! You've just compressed some data! Easy. I saved you hours of mindfuck lectures. This is obviously an oversimplification, but you've transformed some data into another shorter representation of the same information. You've reduced data redundancy. The information entropy in this dataset has not changed - you've just converted between representations. This type of encoder is called an entropy encoder - it's a general-purpose lossless encoder that works for any type of data.

Frequency Domain

Now that you understand information entropy, let's move on to transformations of data. You can represent data in some fundamental units. If you use binary, you have 0 and 1. If you use hex, you have 16 characters. You can easily transform between the two systems. They are essentially equivalent. So far so good? Ok!

Now, some imagination! Imagine you can transform any dataset that varies over space(or time) - something like the brightness value of an image, into a different coordinate space. So instead of x-y coordinates, let's say we have frequency coordinates. freqX and freqY are the axes now. This is called a frequency domain representation. There is another mindfuck mathematical theorem[^2] that states that you can do this for any data and you can achieve a perfect lossless transformation as long as freqX and freqY are high enough.

Okay, but what the freq are freqX and freqY?

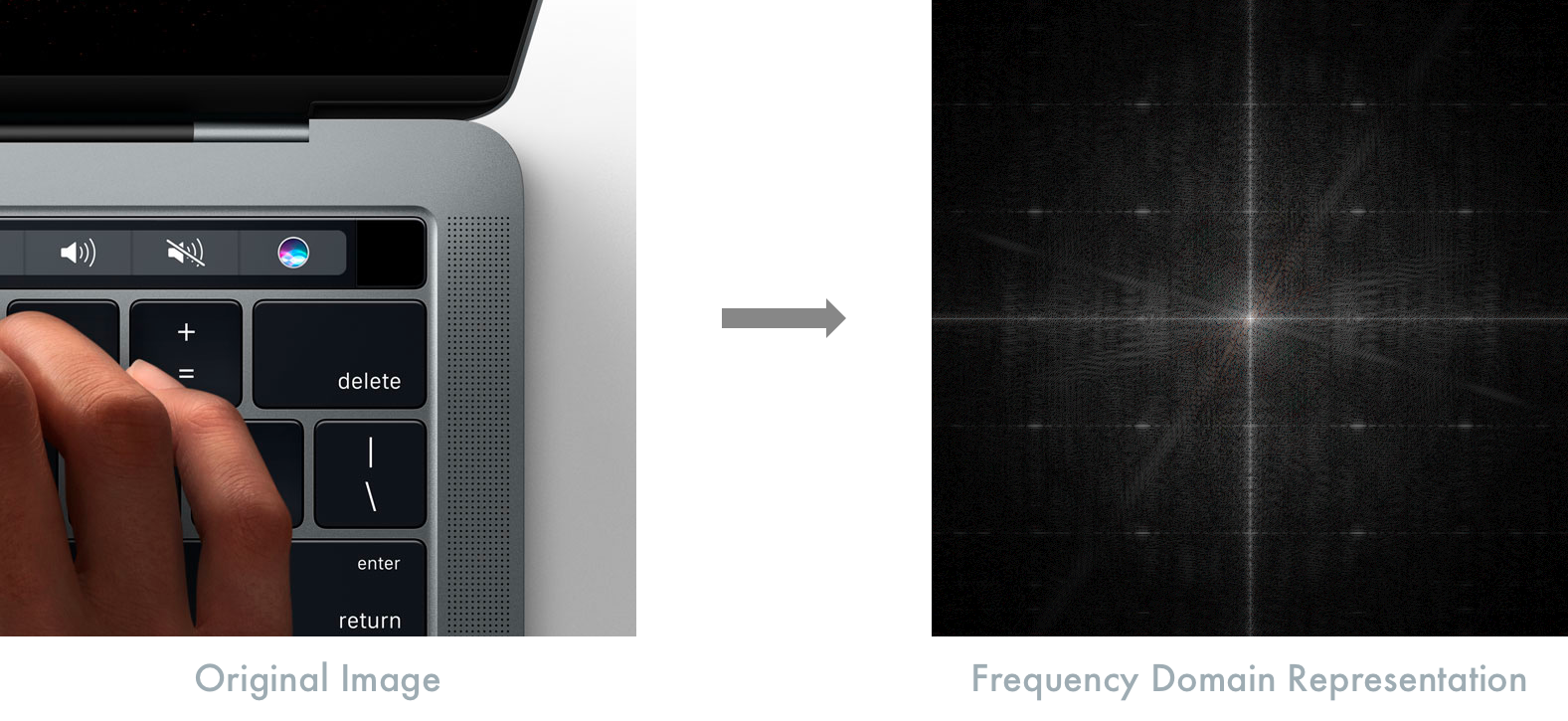

freqX and freqY are some other set of basis units. Just like when we switch from binary to hex, we have a different fundamental unit, we're switching from the familiar X-Y to freqX and freqY. Hex 'A' looks different from binary '1010'. Both mean the same thing, but look different. So here is what our image looks like in the frequency domain:

The fine grill on that MacBook pro has a high information content in the higher frequency components of that image. Finely varying content = high frequency components. Any sort of gradual variation in the color and brightness - such as gradients are low frequency components of that image. Anything in between falls in between. So fine details = high freq. Gentle gradients = low freq. Makes sense?

In the frequency domain representation, the low frequency components are near the center of that image. The higher frequency components are towards of the edges of the image.

Okay. Kinda makes sense. But why do all this?

Because now, you can take that frequency domain image and then mask out the edges - discard information which will contain the information with high frequency components. Now if you convert back to your regular x-y coordinates, you'll find that the resulting image looks similar to the original but has lost some of the fine details. But now, the image only occupies a fraction of the space. By controlling how big your mask is, you can now tune precisely how detailed you want your output images to be.

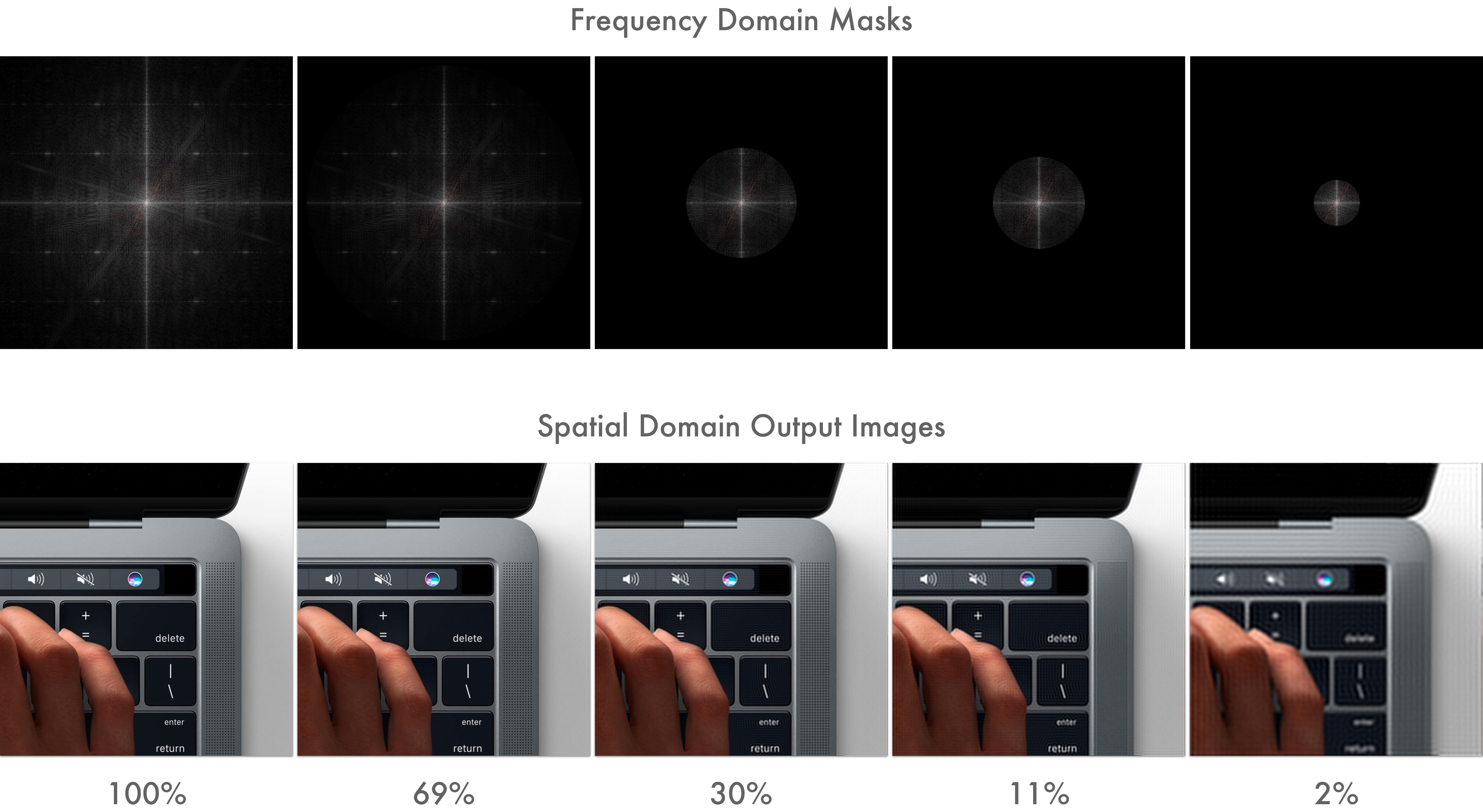

Here is the close-up of the laptop in the home page again. Except now, there is a circular border mask that's been applied.

The numbers represent the information entropy of that image as a fraction of the original. Even at 2%, you won't notice the difference unless you're at this zoom level. 2%! - your car now weighs 60 lbs!

So that's how you shed weight. This process in lossy compression is called quantization[^3].

Okay. Impressive, I guess. What else you got?

Chroma Subsampling.

The human/eye brain system is not very good at resolving finer details in color. It can detect minor variations in brightness very easily but not color. So there must be some way to discard color information to shed even more weight.

In a TV signal, R+G+B color data gets transformed to Y+Cb+Cr. The Y is the luminance (essentially black and white brightness) and the Cb and Cr are the chrominance (color) components. RGB and YCbCr are equivalent in terms of information entropy.

Why unnecessarily complicate? RGB not good enough for you?

Back before we had color TV, we only had the Y signal. And when color TVs just started coming along, engineers had to figure out a way to transmit RGB color along with Y. Instead of using two separate data streams, they wisely decided to encode the color information into Cb and Cr and transmit that along with the Y information. That way, BW TVs would only look at the Y component. Color TVs will, in addition, look at the chrominance components and convert to RGB internally.

But check out the trick: the Y component gets encoded at full resolution. The C components only at a quarter resolution. Since the eye/brain is terrible at detecting color variations, you can get away with this. By doing this, you reduce total bandwidth by one half, with very little visual difference. Half! Your car now weighs 30 lbs!

This process of discarding some of the color information is called Chroma Subsampling[^4]. While not specific to H.264 and has been around for decades itself, it is used almost universally.

Those are the big weight shedders for lossy compression. Our frames are now tiny - since we discarded most of the detail information and half of the color information.

Wait. That's it? Can we do something more?

Yes. Weight shedding is only the first step. So far we're only looking at the spatial domains within a single frame. Now it's time to explore temporal compression - where we look at a group of frames across time.

Motion compensation

H.264 is a motion compensation compression standard.

Motion compensation? What now?

Imagine you're watching a tennis match. The camera is fixed at a certain angle. The only thing moving is the ball back and forth. How would you encode this information? You do what you always do, right? You have a 3D array of pixels, two dimensions in space and one in time. Right?

Nah. Why would you? Most of the image is the same anyway. The court, the net, the crowds, all are static. The only real action is the ball moving. What if you could just have one static image of everything in the background, and then one moving image of just the ball? Wouldn't that save a lot of space? You see where I am going with this? Get it? See where I am going? Motion estimation?

Lame jokes aside, this is exactly what H.264 does. H.264 splits up the image into macro-blocks - typically 16x16 pixel blocks that it will use for motion estimation. It encodes one static image - typically called an I-frame(Intra frame). This is a full frame - containing all the bits it required to construct that frame. And then subsequent frames are either P-frames(predicted) or B-frames(bi-directionally predicted). P-frames are frames that will encode a motion vector for each of the macro-blocks from the previous frame. So a P-frame has to be constructed by the decoder based on previous frames. It starts with the last I-frame in the video stream and then walks through every subsequent frame - adding up the motion vector deltas as it goes along until it arrives at the current frame.

B-frames are even more interesting, where the prediction happens bi-directionally, both from past frames and from future frames. So you can imagine now why that Apple home page video is so well compressed. Because it's really just three I-frames in which the macro blocks are being panned around.

Let's say you've been playing a video on YouTube. You missed the last few seconds of dialog, so you scrub back a few seconds. Have you noticed that it doesn't instantly start playing from that timecode you just selected. It pauses for a few moments and then plays. It's already buffered those frames from the network, since you just played it, so why that pause?

Yeah that annoys the shit out of me. Why does it do that?

Because you've asked the decoder to jump to some arbitrary frame, the decoder has to redo all the calculations - starting from the nearest I-frames and adding up the motion vector deltas to the frame you're on - and this is computationally expensive, and hence the brief pause. Hopefully you'll be less annoyed now, knowing it's actually doing hard work and not just sitting around just to annoy you.

Since you're only encoding motion vectors deltas, this technique is extremely space-efficient for any video with motion, at the cost of some computation.

Now we've covered both spatial and temporal compression! So far we have a shitton of space saved in Quantization. Chroma subsampling further halved the space required. On top of that, we have motion compensation that stores only 3 actual frames for the ~300 that we had in that video.

Looks pretty good to me. Now what?

Now we wrap up and seal the deal. We use a traditional lossless entropy encoder. Because why not? Let's just slap that on there for good measure.

Entropy Coder

The I-frames, after the lossy steps, contain redundant information. The motion vectors for each of the macro blocks in the P and B-frames - there are entire groups of them with the same values - since several macro blocks move by the same amount when the image pans in our test video.

An entropy encoder will take care of this redundancy. And since it is a general purpose lossless encoder, we don't have to worry about what tradeoffs it's making. We can recover all the data that goes in.

And, we're done! At the core of it, this is how video compression codecs like H.264 work. These are its tricks.

Ok great! But I am curious to know how much our car weighs now.

The original video was captured at an odd resolution of 1232x1154. If we apply the math here, we get:

5 secs @ 60 fps = 1232x1154x60x3x5 => 1.2 GB

Compressed video => 175 KB

If we apply the same ratio to our 3000 lb car, we get 0.4 lbs as the final weight. 6.5 ounces!

Yeah. It's magic!

Obviously, I am massively oversimplifying several decades of intense research in this field. If you want to know more, the Wikipedia Page is pretty descriptive.

Have comments? Did I get something wrong? Not a fan of the lame jokes? Offended by the swearing? Use HackerNews or Reddit for voicing your opinion!

Or hit me up on Twitter or LinkedIn if you want to chat.

[^1]SSD Benchmarks

[^2]Nyquist-Shannon Sampling Theorem

[^3][Quantization](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantization_(signal_processing)